As the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation realigns its TB vaccine strategy to focus on early-stage candidate development, equitable access priorities must also be established before large-scale trials are conducted.

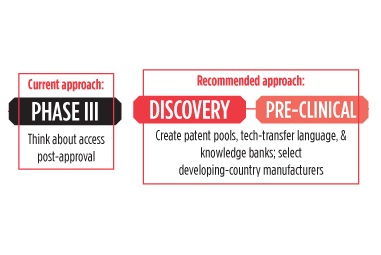

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation has revised its TB vaccines strategy, calling for a “shift to the left” in TB vaccine research and development (R&D). Accordingly, resources will transfer from a limited number of expensive, late-stage phase IIb/III trials to basic discovery, pre-clinical development, and phase I studies to explore a broader range of vaccine concepts. Missing from this shift, however, are plans for ensuring that new vaccines under development will be equitably available to the communities hit hardest by TB.

As the largest funder of TB vaccine R&D globally, any move by the Gates Foundation will ripple across the field. Its new strategy recognizes that only candidates with a high probability of success should enter phase II and III trials, which depend on a rational selection process based on rigorous immunology work on a wider field of candidates in phase I. Focusing resources on earlier stages of R&D will enable the investigation of many vaccine concepts with less financial risk attached to any particular failure.

This intention to “shift to the left” comes at a critical juncture in the fight against TB. After years of unambitious targets, in May 2014, the World Health Assembly (WHA) endorsed the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) End TB Strategy, with its goal to achieve TB elimination by 2035. The third pillar of the End TB Strategy—“intensified research and innovation”—warns that new tools to fight TB, including new TB vaccines, must be introduced no later than 2025 in order to reach the 2035 elimination target. For TB vaccine R&D to match this pace, the field must head ambitiously in new scientific directions, which makes the turn to basic science and pre-clinical work a welcome development.

Scientific limitations continue to cast long shadows of doubt over the path TB vaccine R&D has followed since its revitalization 15 years ago. For example, most of the 15 TB vaccine candidates under development target a narrow, overlapping repertoire of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) antigens—meaning that vaccine developers are betting on a limited number of strategies. Also, common measures used to judge vaccine efficacy in clinical trials (i.e., levels of T-cell cytokines like IFNy) appear necessary, but are not sufficient indicators of protective immunity. Additionally, modest levels of protective immunity demonstrated in animal models have not predicted vaccine efficacy in human trials. These issues boil down to an incomplete understanding of how MTB evades, parries, and turns the human immune response to its advantage. Without this knowledge, designing a safe and effective new TB vaccine becomes too daunting a challenge to overcome by following the empirical (trial-and-error) method used to develop most existing vaccines.

Development-as-usual won’t cut it, so the Gates Foundation’s revised strategy outlines four objectives to guide a new approach: 1) conduct basic science research to understand the natural immune response to infection and disease; 2) develop new vaccine concepts that embrace immunologic diversity; 3) test these concepts through a process of iterative learning; and 4) increase coordination and collaboration. Such a strategy would move the point at which researchers learn whether a vaccine concept will likely work from the most expensive phase of research (i.e., late-stage trials) to pre-clinical development and phase I, where studies are smaller and less costly.

Focusing on early science also presents an opportunity to ensure equity in later stages of R&D, and there are specific steps scientists, sponsors, and funders can take to prepare for access on several fronts. Two important areas for action include anticipating intellectual property obstacles and enabling developing-country vaccine manufacturers to enter the market swiftly after vaccine licensing.

Past experience demonstrates that the market entry of multiple vaccine suppliers—including non-originator companies based in middle- and low-income countries—can expand vaccine access in a timely, affordable manner. Typically, more than a decade can elapse between the introduction of a new vaccine in high-income countries and its rollout in low- and middle-income countries. The Global Vaccine Action Plan, endorsed by the WHA in 2012, sets a target for all immunization programs to have sustainable access to recommended vaccine technologies within five years of licensing. In the case of new TB vaccines, any delay past this five-year window would jeopardize the WHO’s goal of reaching TB elimination by 2035.

Over the next five years, as TB vaccine R&D embraces the new approach, it should develop the intellectual property governance required to introduce any new TB vaccine in endemic countries in time to fulfill the vision of the WHO’s End TB Strategy. Achieving these related goals will require forming patent pools, knowledge banks, and technology transfer platforms. The potential of these structures to expand vaccine access has been outlined by Sara Crager in the July 2014 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, but it holds particular relevance for TB vaccine R&D.

Intellectual property protections have introduced an element of prospecting to even basic science research. New TB vaccines may be a decade or more away, but the future is already owned. An ongoing study by the WHO and the World Intellectual Property Organization has observed a sharp rise in the number of patent applications on vaccine technologies over the past 20 years, with over 9,000 filed between 1990 and 2010. Many of these patent applications apply to HIV and TB vaccine technologies and together compose a dense intellectual property landscape that will shape the accessibility of new vaccines.

Patents, however, are not the only obstacles to ensuring equitable access to new TB vaccines. Unlike many drugs, which non-originator companies can produce generically through reverse engineering, vaccines belong to a class of medical products called biologics that have a more complex construction. Consequently, developing-country manufacturers will, in all likelihood, require transfer of technology, industrial know-how, and nonrestrictive intellectual property provisions from originator companies to manufacture a new TB vaccine.

Agreements on patent licensing, technology transfer, and knowledge sharing involve stakeholders with divergent motivations and require time to establish. Under the “shift to the left” approach, as vaccine concepts develop into vaccine candidates, funding could be made contingent on licensing all patents into a patent pool. Templates for technology transfer from vaccine developers to developing-country manufacturers should be developed at this early stage. All of these mechanisms will need to be hosted by an organization that can convene the diverse stakeholders in TB vaccine R&D—originator companies, academic institutions, private and public funders, manufacturers, civil society, and people with TB.

The “shift to the left” envisioned by the Gates Foundation recognizes that the scarcity of resources in TB vaccine R&D—only $95 million spent globally in 2013, according to resource-tracking by TAG—makes it imperative to allow concepts to fail early—before failure becomes expensive. Overcoming intellectual property barriers and developing channels for technology and knowledge transfer would also lower the risk associated with vaccine development for the public and TB-affected communities around the world that will shoulder the majority of R&D costs. Addressing these issues at an early stage of scientific development will be essential for achieving TB elimination by 2035.

Source: TAGline Spring 2015