Is domestic finance the future of TB financing?

While international financing for TB has grown since 2002, it remains a paltry sum compared with the vast amounts of money channeled to other infectious diseases, such as HIV and AIDS.

24 July 2015 -- One of the biggest complaints by anti-TB advocates has been the lack of new tools to aid them in the fight against tuberculosis, a centuries-old disease that continues to take the lives of an estimated 1.5 million people every year.

And it’s not difficult to understand why. Given all the money, information and technology available today, there is just one tuberculosis vaccine and only for children. Drugs to treat the disease are increasingly facing more aggressive and resistant bacteria. And microscopes continue to be the primary tool to detect TB in most countries — the same tool German physicist and Nobel Prize recipient Robert Koch used when he discovered the bacteria that causes tuberculosis in 1882.

Unfortunately, it is precisely the lack of money and adequate tools that brought the fight against tuberculosis to a standstill. While international financing for TB has grown since 2002, it remains a paltry sum compared with the vast amounts of money channeled to other infectious diseases, such as HIV and AIDS.

Based on estimates by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, aid that went to TB activities reached $1.37 billion in 2014. In the same year, funding for HIV and AIDS totaled $10.9 billion.

A shift in finance options

It is difficult to determine why funding to control and eliminate tuberculosis has remained small. But Dr. Lucica Ditiu, executive director of the Stop TB Partnership, believes the lack of engagement by infected people and the limited ambition attached to its elimination are contributing factors to donors’ lukewarm support.

Unlike with HIV and AIDS, there has been no huge movement calling for the beginning of the end of tuberculosis.

In response to lackluster support from the international donor community, advocates have turned their attention toward domestic resources. In the World Health Organization’s global TB report in 2014, the U.N. health agency argued that given current estimates, 80 percent or $6 billion of the required $8 billion financing for TB in 2015 “could be mobilized from domestic resources.”

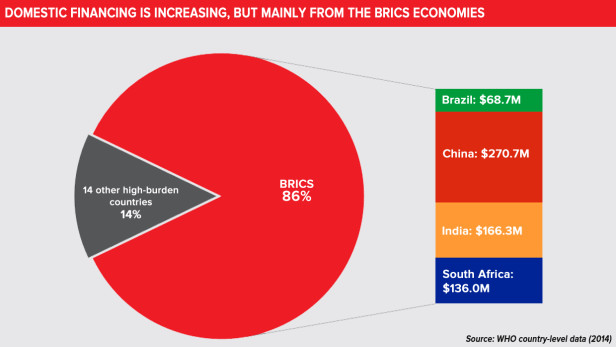

In 2014, based on WHO estimates, almost 90 percent of total global TB financing came from domestic resources.

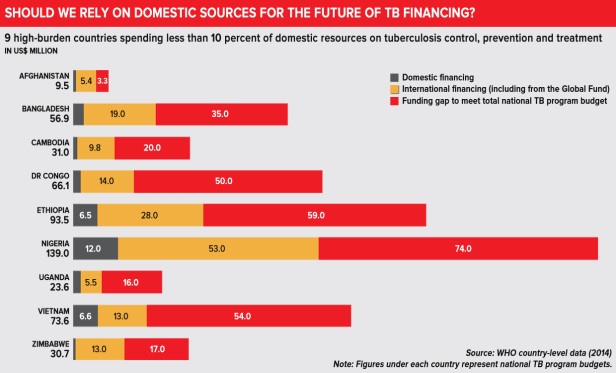

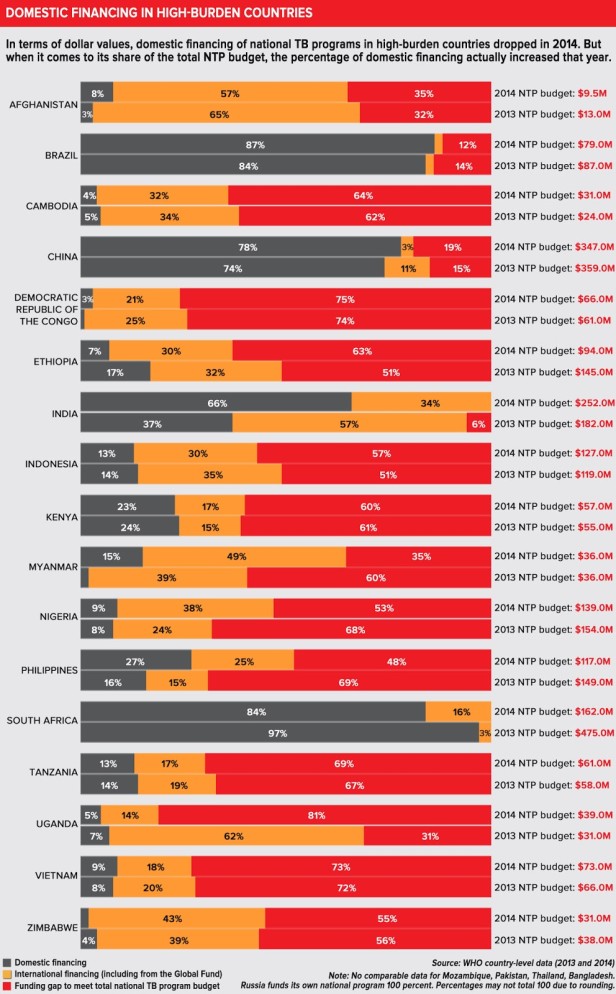

A closer look on domestic spending by countries with a high burden of TB, however, reveal that the majority of them continue to rely on international finance for their anti-TB efforts.

The domestic spend of countries like Kenya and the Philippines, meanwhile, are not as large as that of the BRICS countries, which have tipped the balance between international finance and domestic spend.

International financing for three of the BRICS nations — Brazil, India and China — are dwarfed by the sum of their own national spending. Russia meanwhile is shouldering 100 percent of its $1.83 billion national TB program.

It is because of this disparity that Ditiu warns against jumping into conclusion that low- and middle-income countries can and should be expected to cover a larger portion of the costs of their own tuberculosis programming.

“It is true there are countries that have the financial capacity to properly fund their TB programs, [but that is] if health and TB is a priority for them and they understand the needs, But you cannot suddenly tell countries overnight or from one year to another to go and take over everything,” she told Devex. “It’s not possible and feasible.”

A country that relies on grants from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria for 60 percent of its TB programming, for example, cannot be expected to immediately fill the gap, and she suggested a period of transition is needed.

Overreliance on one platform

That said, Ditiu argued donors should not put all their eggs in one basket when it comes to sending support to countries for their anti-TB efforts.

At present, about 80 percent of international finance for tuberculosis comes from the Global Fund. And in some countries, Global Fund financing represent 90 percent of their programming — underscoring the importance of replenishing the fund.

“So for TB, it’s Global Fund or none,” she quipped.

The aid official is however not satisfied with tuberculosis’ share of the Global Fund’s budget. For the period 2014-2016, the Global Fund’s budget exceeds $16 billion. Of this, only 18 percent has been allocated for tuberculosis.

She also fears current discussions at the Global Fund board, which is considering to focus support on high-impact countries, may pose problems later on: Middle-income countries that still have a high burden of tuberculosis might be made ineligible for Global Fund grants.

“There is a possibility, a very ugly and horrible one, that [financing] will decrease for some TB burdened countries. So we are in continuous dialogue … but I don’t know how it will really play out,” she said.

Other financing avenues

Given this scenario, Ditiu acknowledged the need for finding “innovative financing” for TB, that catchall term that has been used and abused in discussions on development finance.

But one area she thinks stands out is the involvement of the private sector, particularly in research and development and in service delivery.

“I think the private sector is so restless in finding the low hanging fruit that they can use, and I think we can use their restlessness in working together to get and find people and offer them services,” she said, noting that in their experience working with private companies, they’ve been very helpful in finding vulnerable people the partnership isn’t able to reach.

Getting more private sector actors on board is no easy feat, however, and may perhaps be as difficult a task as keeping the world’s attention on the need to eliminate tuberculosis in the next two decades.

“We need to keep the attention of the world, and not have it diluted. That would be a hell of a big job, as there are so many competing priorities. [In addition], we, who are supposed to defend and fight for it, are also poor. It’s like you go to a war, and you fight with someone with a cyborg, and I fight with a knife,” Ditiu said.

She notes how her organization’s funding is “pathetic,” as it has not allowed it to roll out robust advocacy and communication campaigns, which would allow it to also grow its network of TB ambassadors and encourage ideas or new ways of thinking in handling TB.

“We continue to do the same” in their efforts to control, prevent and treat tuberculosis because “we don’t have adequate funding to support” new approaches, Ditiu explained.

The ‘talk’ on domestic resource mobilization

Domestic finance will, however, remain an important topic not just for tuberculosis but for other health issues as well. And Ditiu admits it will be extremely important, especially as the international development community shifts the discussions post-2015 to sustainability.

At the recently concluded International Conference on Financing for Development in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, domestic resource mobilization took the spotlight.

“The ability for us collectively to chase and make sure governments understand the [health] needs of their people and put money into it will be extremely important,” she explained. But the key here, she added, is to not push governments in different directions and expect them to boost domestic financing in all health concerns. “People will end up in a big mess in which it’s very unclear for the government how they should move.”

Source: Devex