US TB drug shortages highlight global gaps

“Our worst enemy is success. We don’t handle success well. We handle crisis well.”

This is how small the world of infectious diseases can be, and how recent the distant past.

The patient who ended up at Baltimore’s Health Department in April 2011 had been treated with apparent success for tuberculosis before, in Kenya, where he was from. But now, he had a strain of the disease that was resistant to all first line drugs. While medical advances had made tuberculosis curable during the century since Baltimore’s “Lung Block” was cited for a death rate that was “little short of appalling,” the odds against this 34-year-old man last year were steep. That was even before the drugs he needed ran out.

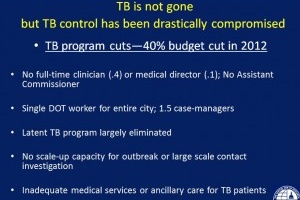

Put in prolonged home isolation necessary to keep him from spreading the drug-resistant disease, he lost his job and his health insurance in short order.The treatment he would need over the next two years is harsh and must be taken with food as well as with strict adherence, but with about 90 tuberculosis patients that year, the city’s TB program relied on one worker to deliver the directly observed treatment necessary to effectively address the disease.

Then, a month into his treatment, a shortage of one of the drugs he was taking was announced. In July, while he was still infectious, the supply of the medicine ran out. His treatment was switched to painful, large-volume injections into his muscles, and in the city’s resource-poor tuberculosis program, local anesthetic to make the treatment less agonizing was unavailable. Also unavailable — medicine to treat the violent nausea that was the side effect of the medicine, or a means to monitor his hearing, even though deafness also is associated with the treatment that was necessary not just to save his life, but in the interests of public health.

“We really were torturing this patient,” Dr. Maunank Shah said Friday. Shah is the Medical Director of the Baltimore City Health Department TB Program, and was talking Friday to a meeting to discuss the problem of U.S. and Global tuberculosis drug shortages. The meeting was sponsored by Treatment Action Group, American Thoracic Society, RESULTS, PATH, and the Center for Global Health Policy, which produces this blog. Shah who also is Assistant Professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University, additionally is involved in research evaluating strategies for tuberculosis in resource poor settings in South Africa, Nigeria, Uganda and Baltimore. His conclusion: “The system is broken.”

The drug shortage that affected the patient Shah described is part of a systemic failure, outlined last week in the Centers for Disesase Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. While the meeting was prompted by the impact of drug shortages on budget-decimated state and city tuberculosis programs and their patients, speakers included Dr. Joël Keravec, manager of the Global Drug Facility, an initiative of the Stop TB Partnership to find and fund reliable supplies of quality TB drugs. The effort was founded in response to drug shortages that disrupted treatment. Speakers also included representatives from other state and local tuberculosis programs, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and from CDC’s Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, as well as a former multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patient.

Across those lines they discussed a common theme — that when efforts against tuberculosis are effective, case rates drop, leading to budget cuts that hobble the efforts that worked: burdening staff, limiting disease detection, hindering treatment.

“Our worst enemy is success,” one participant said. “We don’t handle success well. We handle crisis well.”

Source: Science Speaks